After almost 10 years of talking about building networks of physically separated bike lanes on busy streets, Portland seems more or less ready to move.

Theoretically, that is.

Various small projects are already in motion. A downtown network is funded and ready to start public planning. The next mayor won election making protected lanes part of his platform, especially for east Portland. Voters just ponied up enough money to start the work. This week, city staff were in Seattle talking nuts and bolts with peers there.

All of which means that a city memo about the various obstacles to protected bike lanes is revealing reading.

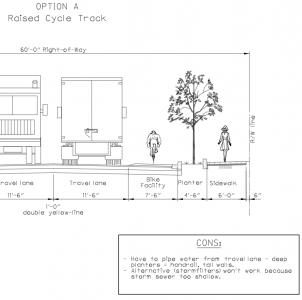

The 75-page “technical memo” by Portland Bicycle Planning Coordinator Roger Geller and colleagues, posted to the city’s website this spring, is at once a trove of good ideas — almost all of it consists of diagrams showing how to fit buffered and protected bike lanes on streets of various widths and uses — and a tally of the hoops Portland requires a comfortable bike lane to jump through.

For example, there’s the 26 feet of open space requested by the Fire Bureau on any street adjacent to a building of at least three stories. That’s enough room for a 10-foot-wide fire truck with an eight-foot outrigger on each side, needed to provide stability for a ladder.

Could one or both of the outriggers straddle a curb or other obstacle that separates bike and auto traffic? Maybe. But it can’t straddle a parked car, which has prevented parking-protected bike lanes on narrow streets like Stark and Oak downtown.

Another obstacle: stormwater. Rain that runs off city streets warms rivers and kills habitats there, so the federal and state governments require cities to add drainage swales and other features to reduce runoff on “projects that develop or redevelop over 500 square feet of impervious surface.” That gets expensive fast.

But as Geller’s memo notes, the city’s storm bureau cuts slack for walking projects like new curb extensions — it waives the requirement for better storm drainage in part because the city doesn’t want to create an “undue burden” on a walking project.

There’s no such waiver practice for biking projects, the memo says.

Another issue: the “step out” area the city generally provides next to a new parking space, for people who move from a parked car to a mobility device such as a wheelchair. As the memo notes, federal standards don’t actually require those extra three feet next to every parking space, only next to spaces set aside for people with disabilities. But Portland’s preference is to provide it on all on-street spaces, potentially reducing the space available for a curb-separated bikeway.

There are many other issues embedded in the diagrams, like turning radiuses for trucks, lane widths for buses and adequate separation between biking and walking traffic.

The memo is a useful reminder of how unfamiliar these designs remain for most city employees — and also of the fact that meaningful changes to Portland’s streets will require a sense of purpose not only within the city’s transportation bureau but the other bureaus, too. That means that ultimately, it’s up to the elected city council to decide if these new designs are worthwhile — and if they are, to tell the public’s employees that they need to take the time to work these issues out.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Our work is supported by subscribers. Please become one today.

The post Separation anxiety: Here’s why Portland isn’t building protected bikeways (yet) appeared first on BikePortland.org.

from Front Page – BikePortland.org http://ift.tt/1UbhOkK

No comments:

Post a Comment